A personal blog by MJA member Jane Feinmann

A personal blog by MJA member Jane Feinmann

If the Cass Review was intended to end the bitter mudslinging over how to manage children and adolescents with gender incongruence, it failed miserably.

Sure enough its main finding — that the prescribing puberty blockers for children and adolescents with gender incongruence, is “an area of remarkably weak evidence based on very shaky foundation” – led to the abrupt closure of the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) and an emergency ban on private and NHS prescriptions of puberty blockers, ordered by Health Secretary Wes Streeting, eight months later.

But bitter critics accuse the Review of ignoring the evidence, with venomous social media campaigns supported by the BMA for several months, and the New England Journal of the Medicine as recently as January 2025.

Higher standards

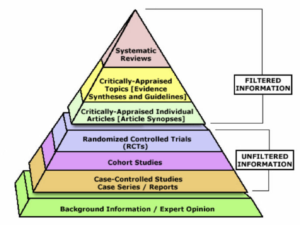

According to the CAN-SG (Clinical Advisory Network on Sex and Gender), a group of clinicians campaigning for higher standards of evidence-based care in transgender medicine, the problem is the widespread failure to take on board the ‘evidence pyramid’.

This ground-breaking tool, first introduced in the early 1990s, demonstrates the hierarchy of evidence-based medicine – supporting safe and reliable clinical decision-making by eliminating “a whole range of psychological biases that we are all subject to, doctors being no exception”, UCL consultant neuropsychologist, Sallie Baxendale, told the recent CAN-SG meeting, After Cass, What Next?

This ground-breaking tool, first introduced in the early 1990s, demonstrates the hierarchy of evidence-based medicine – supporting safe and reliable clinical decision-making by eliminating “a whole range of psychological biases that we are all subject to, doctors being no exception”, UCL consultant neuropsychologist, Sallie Baxendale, told the recent CAN-SG meeting, After Cass, What Next?

Cass’s conclusion, Baxendale explained, was based on seven new and two older systematic reviews, a type of research that stands right at the top of the evidence hierarchy.

Expert consensus

Cass’s critics, on the other hand, reference a very different type of evidence: expert consensus in the form of a series of studies from WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health). This global organisation boasts a membership of “almost 2,000 experts” in the field.

Until the emergence of the EBM evidence pyramid, expert consensus was considered authoritative – with panels of experts refuting the findings RCTs, Baxendale explained. Yet WPATH continues to exert its influence even though expert consensus is now seen as “highly unreliable”, occupying “the bottom rung of the evidence pyramid as the lowest and least reliable category of evidence”. Expert consensus is now known to be responsible for lethal errors in medical research — from “the management of stomach ulcers to sleep position in babies”, she went on.

Meanwhile, a new factor in the row over evidence on prescribing puberty blockers looks set to ensure that debate continues for months, even years. An emergency ban may have been imposed by NHS England last year – but some children and young adults will soon eligible to start on puberty blockers as part of Pathways, a trial that was called for by Cass and for which NHSE has recently announced £10.7m in funding.

Contentious

The Pathways trial is currently awaiting ethical and regulatory approval, including a decision on inclusion and exclusion criteria. That is likely to be contentious, given, as I note in my recent BMJ news story, that ‘pro-Cass’ clinicians are already lining up to express their unwillingness to be involved in supporting under-18s to be included in the trial, given that it will involve starting a treatment that was the subject of an emergency ban by NHS England just a few months ago.

No surprise then that NHS Health Research Agency, the organisation set to consider ethical and regulatory approval for Pathway, acknowledges it’s a “highly politicised area where mis and disinformation is rife”. It remains confident that the trial will go ahead, insisting that its Research Ethics Committee is “well qualified to give this research the due care and consideration that it deserves”. A continuing saga.

A video recording of the CAN-SG meeting is available to MJA members.

Thanks for this.

Of course one problem with this pyramid structure (there are many) is that “critically appraised” is itself a collation of expert opinion, so this will have its own biases and perceived priorities… e.g. NICE which takes pricing into account. Others may take other things. Systematic reviews probably deserve their position, but their structure (and perhaps findings) come down to the decision of the authors, and their publication to that of the journal, its editorial staff and peer reviewers. The idea that “psychological biases “ can ever be entirely removed does not sit easily with me.

Yes thanks for that John, just seen it. You make a good point – and one cognitive bias experts would probably agree with. Sometimes it feels as though what we claim to know about extent of bias in humans including academics is the tip of an iceberg. Would it help to rename the pyramid the ‘cognitive bias pyramid”, reflecting the level of likely bias in the finding rather than claiming to measure the reliability of the evidence?