Founder member, Ronnie Bedford OBE: a tribute by Nick Timmins

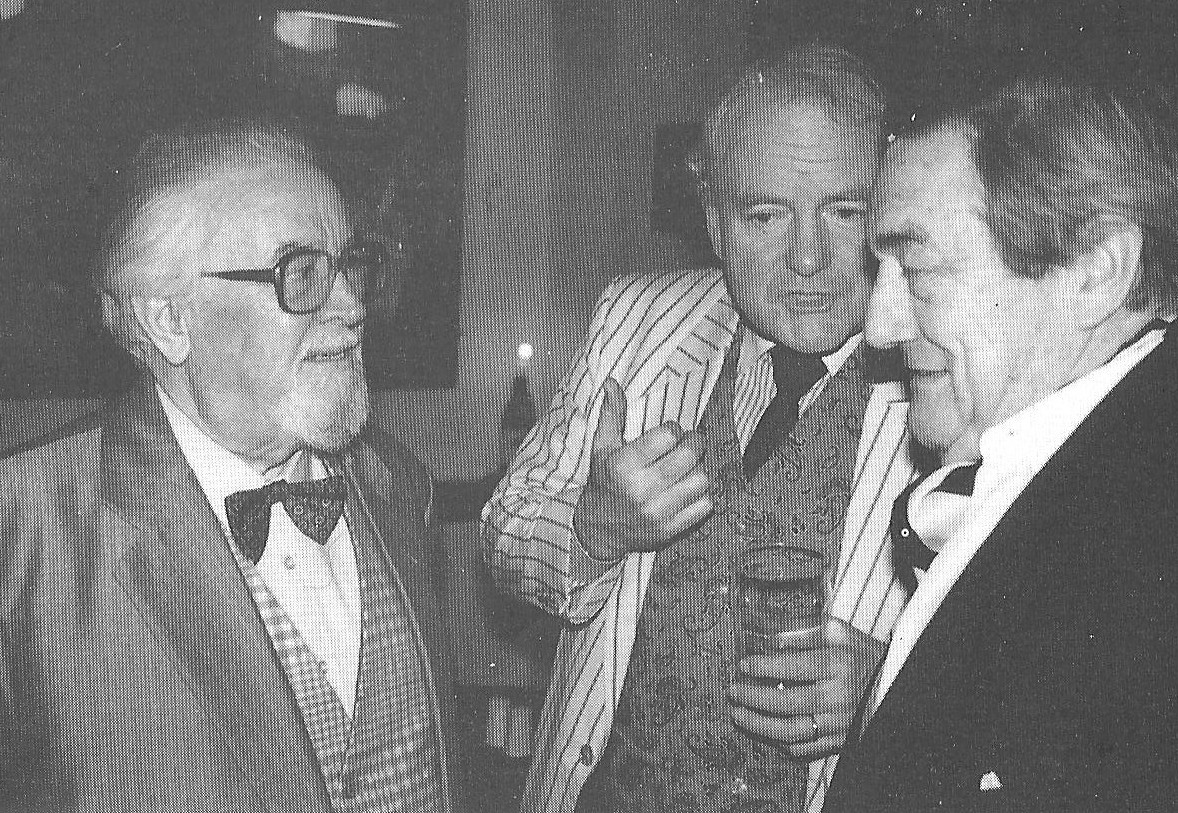

(Picture shows, from left: Ronnnie with David Delvin and Nick Henderson at the MJA’s 30th birthday party in 1997, at the Cheshire Cheese, off Fleet Street.)

Ronnie Bedford, doyen of science and medicine correspondents and one of the great popularisers of the subjects, in the finest sense of the word, has died age 90.

A founder member of the MJA, Ronald Bedford, OBE, was science editor of the Daily Mirror and the Sunday Mirror for almost a quarter of a century, starting in the 1960s at a time when the Mirror sold more than five million copies a day.

Blind in his left eye from birth, with poor sight in his right eye and handicapped by a cleft palate that produced a speech defect, Ronnie never let any of that get in the way either of his journalism, or his remarkable skill as a jazz and, indeed, classical pianist – the jazz being exercised in places as diverse as a Paris brothel and playing on the ice of Antarctica on a visit to the British Polar Expedition..

Born in Walton, near Wakefield, Yorkshire, the county that Ronnie always insisted was ‘God’s own country’, his eyesight meant he could not pursue his first ambition to follow his father on to the footplate of the great steam locomotives of the day. Instead he decided to become a reporter, starting out as an errand boy, sweeping the print shop floor at the Wakefield Express. He became a junior reporter just before the outbreak of World War Two, working on evenings and weeklies in the north before joining the Daily Mirror in Manchester in 1943 and then in 1945 achieving his goal of reaching Fleet Street, where he was first a feature writer and then chief UK reporter for Reuters.

Ronnie rejoined the Mirror in 1947, switching to full-time science and medicine coverage in 1950 before becoming science editor in 1962, a post he held until retirement in 1985.

He held what he described as a ringside seat from which he watched the development of the peaceful use of atomic energy, the discovery by Crick and Watson (aided by Franklin and Wilkins) of the structure of DNA, the arrival of kidney, heart and other organ transplants, the creation of test-tube babies, and the space programme, including the Apollo launches from Apollo 8, the first circumnavigation of the moon, through to Apollo 13 – ‘Houston, we have a problem’ – and beyond.

He used this ringside seat, however, to do much more than watch, interpreting often complex science by the use of great analogy while asking the sorts of question that created great stories. He had a wonderful turn of phrase – once describing the globe of the Dounreay fast reactor as being perched on the edge of Scotland ‘like a golf ball waiting to be driven off into the Atlantic’. He amassed countless scoops, including the death of Laika, the first dog sent into space by the Soviet Union, ahead of humans.

He combined fierce competitiveness with great generosity. When I was PA’s science correspondent, Ronnie arrived after me at a conference where some scientists were describing how they had impregnated imperforated sheets of blotting paper with the ingredients of the contraceptive pill to provide a low-cost product for the developing world. I’d filed. Ronnie looked at my copy, snorted, set off to find the authors and produced a story about ‘the postage stamp pill’ – explaining gently afterwards that that was how it was done.

Among his proudest achievements as a reporter who actually made a difference was his support of the campaign by the ophthalmologist Brian Rycroft that led to the Corneal Grafting Act of 1952 that made it legal for people to donate, and for surgeons to take, corneas for grafting after death. He also played an important part in getting prams redesigned follow the death of Bill Inman’s baby daughter who was strangled by an elasticated mobile toy strung across her pram. (Inman went on to be chairman of the Committee on Safety of Medicines and deviser of the ‘yellow card’ system for reporting adverse drug reactions.)

Ronnie’s journalism for the Mirror literally took him round the world – to Australia, Japan, Israel, French Guiana, Alaska, Greenland, India and the Sahara. At home, he was instrumental in breaking down barriers between the medical royal colleges, the British Medical Association and reporters in the days when the medical profession believed it should dictate what went into the press. He was also chairman of the MJA from 1977-80. MJA honorary member, Paul Vaughan, chief press officer of the BMA in Ronnie’s earlier days, wrote that ‘Many of the (BMA) doctors assumed a patronising and contemptuous attitude towards him, partly because he suffered a speech defect, but mainly because of their lofty assumption that his newspaper, being a popular one, was incapable of reporting serious issues. How wrong they were. His was a skill born of years of experience as a reporter, and of his sharp intelligence.’

He married twice, second time around to Thelma whom he met at the BMA where she was a senior press officer. He is survived by Thelma and also by Helen and Joy, two of the three daughters of his first marriage. He retired to Broadstairs in Kent, where his funeral was held in the Palace cinema, complete with a Wurlitzer organ that Ronnie loved. The mourners were played in to Fly me to the Moon. Ronnie was played out to I do like to be beside the seaside.

If MJA members have recollections or tributes they would like to post, either send them to the secretary in reply to this message, or go online at the website where this will be posted and add your comment in the box at the bottom of the post. At the end of June a tribute to Ronnie with appear in the MJA newsletter, MJA News.

I first met Ronnie in the late1960s when I was looking for a foothold in journalism. He spent time talking to me and was very friendly and full of advice. I will always remember his kindness and his willingness to spend time on a young person with hopes and aspirations. Goodbye Ronnie.

Ronnie got to the human core of everyone and everything. Although I wasn’t there, I remember being told about the first occasion when medical journalists were `allowed’ into a Royal Medical college. It was, I heard, arrogantly assumed that they could be exactly instructed on what they were allowed to pass on to their readers. Our Ronnie wasn’t having any of it. At a word from him, they all got up and left. It was the start of a big change in attitudes.

Ronnie bowled me over at my very first MJA meeting decades ago. He also told me `his’ joke – for the first time! It was about the world’s three most useless objects or sayings – the last of which was `the cheques in the post’. The first two politically-incorrect ones, all long-serving MJA members must well remember.

Ronnie was one of the first to unravel the often unnecessarily complicated explanations of the complexities and mysteries of medicine for the everyday reader. He was among the first to do for medicine what Tyndale did for theology – though without losing his head over it in any sense.

A really great bloke.

Ronnie was a one-off – medical journalist, science journalist, jazz pianist, raconteur, and all-round ‘fixer’ for the science and medical corps. In 1965, a year before the MJA was born, he got wind of an attempt by the BMA to keep the Press out of a controversial session on organ transplants. Tony Thistlethwaite, BMA Press officer at the time recalled that Ronnie nobbled the Association’s secretary and president at a Press reception and offered the commonsense solution that journalists could omit the sensitive part of one paper. The two BMA leaders agreed – and the blanket ban was lifted. Tony wrote afterwards in the MJA’s story, Independent and Bloody Minded: ‘Here was an instance of the Press negotiating firmly and fairly, and they did not need a Medical Journalists’ Association. They had Ronnie Bedford, instead’.

He was a bloody good journalist who could breathe life into the dullest story from astrophysics to zoonoses and produce a sparkling page lead. Typically, he once came across a new medical treatment for pruritis ani (itchy bum). Next day the Mirror ran his story about researchers getting to the bottom of a ‘ticklish’ complaint affecting long-distance truck and car drivers.

It was not only his medical and science journalism that shone. On one occasion he was covering a meeting of the International Astronautical Federation in (I think) Belgrade. Having filed our stories, one evening we were relaxing in a piano bar when the resident pianist went off for his break, much to the relief of the entire room. He was followed to the piano by Ronnie, groping his way in the half-light. Within seconds of his hitting the boogie-woogie bass notes, the talking hushed and the bar was electrified, bursting into enthusiastic applause at the talented jazz musician.

In 1971 while covering a rocket launch of ELDO, forerunner of the European Space Agency, in French Guiana, journalists made a diversion to see the former French penal colony Devil’s Island and it’s neighbour, Isle Royale. While others gathered mangoes which grew in abundance for a (free) champagne party on the flight home, Ronnie proudly took home a hewn rock from the crumbling walls bearing the prison’s moniker. Truly an original – and very heavy – souvenir

A stickler for accuracy despite enforced brevity, it is no surprise that Ronnie himself wrote some of his obit. two years ago. As he might have said: ‘I don’t want someone cocking it up.’ We will all miss him.