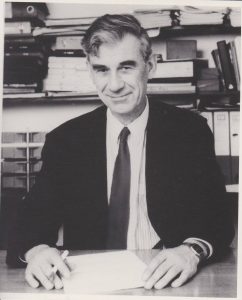

The eminent nutritionist, former EC member, founding member of HealthWatch and tireless opponent of quackery, John Stuart Garrow died at his home in Yorkshire on June 22, 2016. He had been in good health until suffering a stroke six weeks earlier.

John Garrow, who was born in Dundee on April 19, 1929, became professor of nutrition at Bart’s Hopsital in London and a MJA committee member for six years in the 1990s.

Caroline Richmond recalls: “He was well known as an expert on obesity, but few might know he spend the first part of his career studying malnutrition and tropical medicine in Jamaica. He was a trenchant critic of bad science and a beacon of light in a world of nutritional misinformation.

“He designed the weight/height charts that show at a glance where any individual stood on the scale between underweight and obese. He published research on malnutrition, kwashiorkor, trypanosomiasis, protein metabolism in wound healing, and potassium metabolism. He helped develop two devices: calibration of an instrument to measure potassium, and the random-zero sphygnomanometer, designed to outsmart the introduction of errors by the human instinct to round a measurement up or down.

“In 1969, aged 40, he was appointed head of the MRC Nutrition Research unit at the newly formed, but now defunct, Clinical Research Centre attached to Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow. Presciently noting that Britain’s emerging nutritional problem was obesity, he spent the remaining 18 years of his career studying it.”

A former colleague, immunologist David Webster, said of Garrow: “He was a quiet and courteous man who did not push his views on obesity until he had good data from the physiological chamber built for him to measure precisely what went into, and out of, fat people. He came to the conclusion that fat people got fat because they ate too much and did very little; an important conclusion because there was a view in the 70s that these people had some mysterious problem in accumulating fat from thin air.”

In 1987, at the age of 58, John was appointed inaugural professor of human nutrition at Barts and worked long and diligently at his research, clinics, and food policy committees. He worked by night on his textbooks: a co-authored monograph on Electrolyte metabolism in severe infantile malnutrition 1968, Energy metabolism and obesity in man 1974, 1978, Treating obesity seriously: a clinical manual 1981, and Obesity and related diseases 1988. With Philip James he edited several editions Human nutrition and dietetics.

Mandy Payne, his friend and colleague from HealthWatch — the charity which promotes evidence-based medicine and exposes quackery — says: “Ever modest, John would not have appreciated a lengthy or extravagant memorialising of his achievements, but they were many.

“John’s work was characterized by intellectual rigor and honesty, and he wrote with a simple but precise elegance. Edzard Ernst, in his blog of 23 June 2016,1 recalls with pleasure working with him on what may have been the first ever randomised controlled trial of the peer-review system. Sending dummy manuscripts to 400 unsuspecting reviewers solicited a wide range of responses, and the conclusion that reviewers showed a small bias towards the orthodox.

“Peter Wilmshurst remembers John as a champion of the highest ethical standards in medicine and research. They met in 1977 at Northwick Park Hospital — John designed and funded a study that Peter was researching, but when it was finished John declined to put his name on the paper. He said that he thought that he had not contributed enough. John’s scruples over the amount of contribution required for authorship were admirable and, sadly, unusual.

“A decade later, when Peter was sued for libel after flagging misleading reporting of the results of a clinical trial, John had HealthWatch set up a whistleblower support fund, priming the fund with a large personal contribution, and attending the High Court hearings to give moral support.

“John had himself had problems with libel issues. Ben Goldacre’s 2008 book “Bad Science” reproduces a courteous letter from Professor Garrow inviting the celebrity nutrition guru Gillian McKeith to subject her “living food powder” to a simple controlled trial of efficacy, adding a gentlemanly wager of £1,000 to boot. The response from the McKeith family was a telephone call from her husband with a threat of legal action for defamation. John, who Goldacre describes as ‘an immensely affable and relaxed old academic’, shrugged it off with the words, ‘Sue me’. She never did.”

However, when MJA Vice Chair, Jane Symons, who was then editing the health pages of The Sun, exposed Mrs McKeith’s lack of credentials in a story headlined ‘DR? NO’ — she did sue, and John was one of a number of expert witnesses who relished the opportunity to provide evidence, along with Ben Goldacre and nutritionist Catherine Collins. Mrs McKeith eventually dropped her claim.

HealthWatch founding member, lawyer, Diana Brahams: recalls: “For many years, HealthWatch meetings were held at Barts’ premises that John arranged without any charge to HealthWatch. John had true gravitas combined with kindness, a wry humour and sharp wit and a huge fund of experience and knowledge. Those who had him as their treating clinician or tutor were very lucky.”

James May, current chairman, adds: “Despite being a great man, he had the heart of a servant, and would routinely ensure that wine cups were kept topped up throughout our meetings. He would say, ‘to prevent blood alcohol dropping to dangerously low levels’, and who was I, given his credentials, to ignore these dire warnings?”

And Mandy Payne, who attended John’s funeral adds: “I learnt that he had for many years indulged his scientific curiosity by using himself as a n=1 trial subject—when he first met his wife Katherine he was experimenting with the azo dye Evans blue as a tracer for human plasma albumin. It had turned his skin blue. I also learnt that he played the cello — not well, by all accounts.

“We toasted John Garrow with cups of tea (he liked it with plenty sugar) and his favourite meal — a mountain of deep-fried scampi followed by freshly baked scones heaped with jam and fresh cream.”

In an era when nutritionist is all to often used to describe individuals with no credible academic qualifications recommending any number of fads and fallacies, a truly great nutritionist who also enjoyed the simple pleasures of scones and scampi will be sorely missed.

Recent Comments