Science writer and broadcaster Geoff Watts reviews The Least Likely Man: Marshall Nirenberg and the Discovery of the Genetic Code by Franklin H. Portugal. Published by the MIT Press.

If asked before reading this book to name the first ten people that come to mind for their contributions to post war molecular biology my list might have gone something like this: Francis Crick and James Watson (obviously) followed by Sydney Brenner, Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, Fred Sanger, Max Perutz, John Kendrew, Max Delbruck, and Jacques Monod. The list (ordered not for the importance of their work, but simply as I thought of them) wouldn’t, I think, have included Marshall Nirenberg. Yet he won a Nobel Prize in 1968 for his part in interpreting the genetic code.

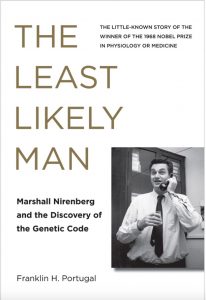

Nirenberg is now the subject a biography by scientist Franklin Portugal titled The Least Likely Man. It opens with Portugal’s claim that Nirenberg is “the most famous person you have never heard of.” Well, I’d not only heard of him; I’d written his obituary for The Lancet when he died just over five years ago. But mindful of my opening list I take Portugal’s point. Although Crick and Watson’s insight into the mechanism of heredity was the towering achievement of 20th Century biology, the means by which the information contained in DNA was read, interpreted, and used to specify the make up of the proteins that give it effect was a close second. So it is odd that Nirenberg wouldn’t have been in my top ten — not because he doesn’t deserve to be, but just because he doesn’t come to mind. Why is he so little known?

Nirenberg is now the subject a biography by scientist Franklin Portugal titled The Least Likely Man. It opens with Portugal’s claim that Nirenberg is “the most famous person you have never heard of.” Well, I’d not only heard of him; I’d written his obituary for The Lancet when he died just over five years ago. But mindful of my opening list I take Portugal’s point. Although Crick and Watson’s insight into the mechanism of heredity was the towering achievement of 20th Century biology, the means by which the information contained in DNA was read, interpreted, and used to specify the make up of the proteins that give it effect was a close second. So it is odd that Nirenberg wouldn’t have been in my top ten — not because he doesn’t deserve to be, but just because he doesn’t come to mind. Why is he so little known?

To answer that question is one of Portugal’s aims: one in which I’m not sure he’s entirely successful. Along the way, though, he answers a great many others, and reveals a lot about the mix of hard work and inspiration that put Nirenberg just ahead of his better known rivals, and won him his share of the Nobel Prize.

Nirenberg was not, it seems, a star performer — at school, university, in his early work, and even (initially) at the US National Institutes of Health in Bethesda where he embarked on the task of divining the code by which a superficially random sequence of A,T,C and G bases in the DNA molecule form the recipes for making different proteins. Much more familiar names, including those of Crick and Brenner, were inching their way to an understanding. They had even formed what they called the “RNA Tie Club” with a membership of 20 and limited to those researchers from whom they immodestly assumed the insight would eventually come. Nirenberg was not only outside the group, but barely known to many of them.

Portugal has several things going for him as the author of this book. As a scientist himself he actually worked for two years with Nirenberg, and then become a friend. Besides being able to talk to many of his subject’s colleagues and associates he’s also read Nirenberg’s extensive notes. In addition to lab notes in the usual sense – accounts of experiments performed, results obtained and the like – Nirenberg kept other more introspective jottings in which he reflected on his achievements or lack of them, his state of mind, his ambitions, and his rising determination to solve the problem that was driving him forward.

The book is a mostly readable account from which we learn something of Nirenberg’s life and times outside the lab, of his family, and of his father’s influence in particular. We’re told not only about the experiments that worked, but also the many failures and blind alleys that are an inescapable feature of laboratory life. For some readers I suspect there will rather too much information about Nirenberg’s experimental work. While the sense of excitement is there, it’s occasionally submerged beneath a welter of detail that only a serious historian of science would need to know.

Because Nirenberg was unassuming and didn’t seem destined to become a high achiever, he attracted little attention. He didn’t join the molecular biology elite because even those who knew his work wouldn’t have thought he had it in him to become one of them. And when, de facto, he did, he seems to have had little taste for self-publicity.

As Portugal makes clear, Nirenberg was always passionate about science, and the passion paid off. We understand the sequence of events by which he achieved his outcome, and the determination required to keep going. But why is he not better known? Why wouldn’t he have loomed larger in my mind if I had, for real, been compiling that top ten list. Was it all down to Nirenberg’s modesty? On that one I’m still not fully the wiser.

MJA members can claim a 30% discount on The Least Likely Man and all other MIT Press titles. Click here for details

About our reviewer:

Geoff Watts spent five years in medical research before abandoning an academic career in favour of science and medical journalism. He was science editor and then deputy editor of World Medicine magazine and has presented countless features and series for BBC Radios 3 and 4 – notably Science Now and Medicine Now.

He currently presents Radio 4’s science magazine programme Leading Edge. Geoff has written books on irritable bowel syndrome and the placebo effect, and contributed chapters to two more works on the future of medicine. He divides his time between writing, broadcasting, and media consultancy work. He is also a member of the UK Government’s Human Genetics Commission, and a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences.

And some other views:

J. Craig Venter, Ph.D., first sequencer of the human genome writes: “Marshall Nirenberg is one of the most important scientists of the twentieth century with his key contributions to the discovery of the genetic code. Scientific discoveries are a combination of the right people at the right moments in history with the right insight, and it helps if they are also great experimentalists. Marshall Nirenberg had all of these in spades. Science, like all human endeavors, is also very political. Franklin Portugal in his The Least Likely Man has recounted the historical period that led to our first level of understanding of the genetic code with his portrayal of Marshall’s discovery, political battles, and ultimate triumph in his quest to show how the linear DNA code leads to the linear protein code. Marshall was a friend and colleague and in my view one of the great heroes of experimental science where his data triumphed all politics.”

Joseph L. Goldstein, 1985 Nobel Laureate, Physiology or Medicine writes: “The Least Likely Man engagingly recounts the inside story of how the genetic code was deciphered in the 1960s—not by Watson & Crick and their tribe of brilliant molecular biologists—but by the least likely of scientists (Marshall Nirenberg) who did the least likely of experiments (filter binding assays). Despite its backwater beginnings, Nirenberg’s table of the 64 DNA codons has achieved iconic status as the biologists’ counterpart to Mendeleev’s periodic table for chemists and Einstein’s E=mc2 for physicists—forming the first Holy Trinity for Science.”

Recent Comments