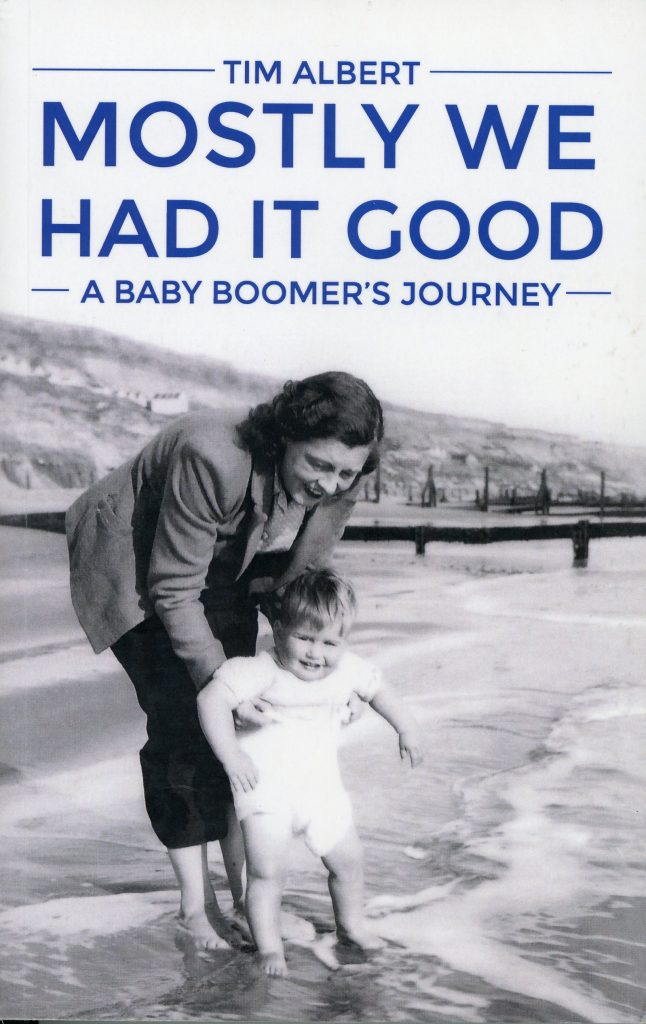

Mostly We Had It Good: A Baby Boomer’s Journey, by Tim Albert, reviewed by Michael O’Donnell.

When Tim Albert told his friends that he was writing an autobiography some asked, as politely as they could, why on earth was he doing it? The book gives them their answer. Tim had discovered buried treasure. And that’s why his story is such an entertaining and compelling read.

Like many a journalist, Tim is a hoarder. Some of us are loathe to throw away any piece of paper graced with sentences we have created but Tim was a hoarder long before he became a journalist. We should bless the day he realised it was a inheritable condition and that, squirrelled away in rarely visited corners of his house, were not just his own hoardings but those of his family including his great-grandfather’s spectacles and a phrenological analysis of the old man’s character.

Like many a journalist, Tim is a hoarder. Some of us are loathe to throw away any piece of paper graced with sentences we have created but Tim was a hoarder long before he became a journalist. We should bless the day he realised it was a inheritable condition and that, squirrelled away in rarely visited corners of his house, were not just his own hoardings but those of his family including his great-grandfather’s spectacles and a phrenological analysis of the old man’s character.

There were menus from transatlantic liners, boxes of letters Tim’s father had written as a child, community newsletters from the General Strike, his mother’s school scrapbook and her School Leaving Certificate, Tim’s schoolboy diaries, poems he wrote for the school literary magazine, articles he had written, notes he had made on this travels, scrapbooks and photo albums… a serendipitous collection of artefacts that documented the history of the family into which he had been born and of the life that he had lived.

These artefacts, skilfully embedded in the story Tim tells us in Mostly We Had It Good: A Baby Boomer’s Journey, enhance its authenticity and ensures that it never lapses into mere nostalgia.

The first part of the book is a gentle and beguiling tale of ‘comfortably-off’ middle class family life in post-war Britain. Tim’s father was a partner in a small firm of solicitors with offices near the Bank of England and a member of a generation that, inspired by opportunities created by the invention of the internal combustion engine, chose to move from the smoky city to the romantic ‘countryside’ where people would find less noise and fresher air.

At the dawn of the 1950s, when the Alberts moved from Earl’s Court to Wimbledon Village, it really was a village not yet engulfed by suburbia. One couple living in Chelsea used to travel all of six miles to spend the weekend at their ‘country cottage’ on the edge of Wimbledon Common. The village on the hill, Tim writes, was ‘a magnet for the professional classes, rising above the less prosperous suburbs that provided the chauffeurs and daily helps that kept them comfortable’.

Tim and his elder brother David saw less of the village than their parents. They were sent away to boarding school and Tim offers an undecorated account of the sort of education you receive when nearly all your teachers are members of a religious order: nuns when he was very young, Benedictine monks when he was older.

The second part of the book ranges across territory more familiar to members of the MJA: Tim on a training scheme inaugurated by Hugh Cudlipp which involved a spell as a trainee reporter on a local newspaper in Devon and as a sub on the Sunday Mirror, his work on the Times Educational Supplement and New Society, his time as the New Statesman’s education correspondent, as World Medicine’s executive editor and editor of BMA News Review.

There are more exotic episodes when Tim trains journalists in the Bahamas, works as a reporter on the Pasadena Star News in California, joins a team of that produces a daily newspaper during the United Nations World Population Conference in Ceausescu’s Bucharest and, along the way, meets a New Yorker called Barbara whom he will later marry

We learn how trainee Tim ate bacon sandwiches in an office at the Tavistock Times beneath a sign declaring ACCURACY IS EVERYHTING and that the first formal lesson taught to trainees at the Sunday Mirror was how to compile an inflated, yet convincing, expenses claim.

For members of the MJA, one the book’s treasures will be Tim’s account of life within the BMA Secretariat. He is one of only two journalists I’ve known who worked for the BMA — not the BMJ, the distinction is essential — and not only survived within the political labyrinth but actually achieved something before emerging with relatively minor wounds.

His account of what went on behind the scenes is essential reading for any journalist taxed with reporting or even, may the Lord have mercy on them, trying to analyse what goes on in the impressive building in Tavistock Square. With remarkable prescience, the architect Edwin Lutyens provided it with what one guide book calls ‘an enigmatic facade’, a feature that, in my time, was adopted by many who worked therein.

There’s a delicious epiphany when Tim as editor of BMA News Review, eager to get the magazine talked about and increase the readership, shows a mock-up of a provocative front cover to the BMA Secretary Ian Field.

‘You can’t publish this,’ says Field.

‘Why not?’ says Tim.

‘We could have letters about it.’

During his stint at the BMA our hero discovers his talent not just for teaching, but as a teaching administrator, and organises highly successful courses teaching doctors, NHS managers and other putative ‘communicators’ how to write clearly and, if they feel the need, to produce newsletters.

When he leaves the BMA he turns the design and provision of training courses into a flourishing international business. And when the business falters a Deus ex machina descends, as always unexpectedly, and magically resolves the problems facing Tim and Barbara.

The Deus is a charming man from The Netherlands ‘with a clipped moustache and military bearing’ but, as is often the case, it’s the machina that does the business. I’m reluctant to publish a spoiler so if you’d like to know more, you’ll have to read the book.

It’s never easy to review the work of people you know as well as I know Tim. There’s a double jeopardy involved: the fear of being overindulgent provokes a fear of being overcritical.

Yet one thing I know for certain is that I enjoyed reading this book.

And I think I know why.

Tim’s story, unlike many autobiographies, is not a mere collection of fond and less fond memories. Each episode is tethered to reality by evidence retrieved from his treasure trove. He writes like a journalist who has access to the Albert family hoard and is writing the biography of a subject who just happens to be himself.

The result is that when he describes events that he and I have witnessed separately the image he creates is much richer in detail than the one in my memory. One effect of this is that, as I read, I find myself reflecting on my own life in the way that I do when I read David Kynaston’s social histories of post-war Britain or Nick Timmins’s biography of our welfare state.

It’s a rewarding experience and I’m grateful to Tim for creating it.

Recent Comments