Oliver Gillie’s death has jolted me. As one of the few survivors (along with John Illman and Peter Pallot) of the foundation years of the MJA, I’d like to share the feeling of those early years with you all. Your founders were special people, bound together by an ethos that has stayed with me in the years to come, and that I still cherish.

But to start at the beginning. In 1972 I was medical adviser to Duphar Laboratories, now a long forgotten pharmaceutical company owned by the Dutch company Philips. My job was to run the clinical trials of new drugs and to try to get the Committee of Safety of Medicines to licence them. I had left seven years of single-handed general practice in rural Scotland to do this, mainly for family reasons. Looking back, I often wonder why I did it: Southampton was a world away from South Ayrshire, and the job took me into business and away from patients. It also took me into writing.

One day the Pulse team came to visit us. The meeting was commercial – Pulse wanted Duphar’s advertising, and Duphar wanted to reach the vast majority of GPs to whom it was delivered free. Out of courtesy I was asked along to lunch, although I had no role to play in the commercial games. I sat beside a small slim man who had as little to contribute as I had. He was Pulse’s Hertzel Creditor. He was curious about why I had so fundamentally changed my career and lifestyle, and I confessed all, adding a few anecdotes about my practice. He invited me to write them down and send them to him, and over the next few days I obliged.

I heard no more from him, until three weeks later I was cleaning out my children’s guinea pig cage, when I noticed some pages of Pulse lying, ordure-stained, under the straw. The children had chosen it for the bedding. On one page was an article by a Dr Desmond Weatherly. I was astonished to read my own words. How could Hertzel have betrayed me so badly?

A short phone call quelled my anger. Herzel explained that the GMC did not allow doctors to write under their own name, as this would be advertising. Desmond Weatherly was the name next in line for Pulse’s doctor contributors: did he not tell me? Oh yes and the £5 payment was in the post.

Hertzel became a good friend. From short stories about rural practice he asked me to switch to the clinical page, where I cut my teeth on the Pulse of Medicine paragraphs (POMs). That was simple. He sent me copies of articles from the main journals for me to summarise in a single paragraph. Sounds difficult? No, he said. Just change the abstracts around a bit! That I managed, and suddenly I was a clinical writer, earning a pound a para. Sadly, I didn’t have his friendship for long. Within a year I was visiting him in hospital where was dying from bile duct cancer. His disease had turned his skin to a deep yellow-green, but he could still laugh about himself. It was at a time when I was pondering my future in industry, and I took his last piece of advice – which was to go back to practice part time and concentrate on my writing. I have never had better advice.

Hertzel had introduced me to my first MJA meeting. I can’t remember the speaker or the subject, but I do remember the people I met there. I had been to many doctors’ meetings, and to meetings of people in the Pharma industry, and was often dismayed by the way the participants so often pressed their own interests. Money, self-advancement, and competition marked so many of them. Not so the members of the infant MJA. Tony Thistlethwaite, the secretary, was one who helped set the MJA ideals in stone – his “Independent and Bloody Minded” book of the MJA in 1997 perfectly described those early days, and I hope it still does today.

Hertzel had introduced me to my first MJA meeting. I can’t remember the speaker or the subject, but I do remember the people I met there. I had been to many doctors’ meetings, and to meetings of people in the Pharma industry, and was often dismayed by the way the participants so often pressed their own interests. Money, self-advancement, and competition marked so many of them. Not so the members of the infant MJA. Tony Thistlethwaite, the secretary, was one who helped set the MJA ideals in stone – his “Independent and Bloody Minded” book of the MJA in 1997 perfectly described those early days, and I hope it still does today.

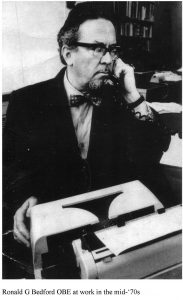

My favourite then was Ronnie Bedford, blind in one eye and almost blind in the other, with a speech defect because of a poorly repaired cleft palate as a child, who was the Mirror’s Science Editor and chief medical reporter. He had to hold up text to an inch or two of his one seeing eye, but he still managed to be at the top of the journalist tree for more than fifty years. Amazingly he was also an accomplished jazz pianist. His obituary in 2012 related that he had fulfilled two ambitions – to play the piano at a famous brothel in Paris, and at the South Pole, when members of the British Polar Expedition dragged a piano across the ice for him! A lovely man.

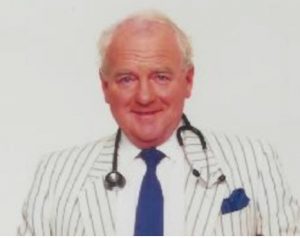

Dr Desmond Weatherly didn’t last long. I thanked David Delvin for that, and so should have any doctor wishing to write under his or her own name. David dared to write an article under his own name and challenged the General Medical Council to strike him off for such a heinous crime. To our surprise, he won! I killed off Dr Desmond, and I became Tom Smith at last. David deserved huge credit not just for that but for the many campaigns he initiated and supported. John Illman’s obituary of David in 2018 was a wonderful summary of a life so well lived, but I have so many private memories of him as a colleague and friend, perhaps because we both had Scots-Irish ancestry. We often bounced ideas off each other, and the Celtic connections were part of that.

David Delvin

Another of the Celtic persuasion was the wonderful Michael O’Donnell. Every GP in Britain in the seventies knew of and laughed with Finnbar Aloysius O’ Flaherty, his counterpart GP in the imaginary northern town of Slagthorpe. Dr Finnbar inhabited the pages of World Medicine, by far the most successful and most widely read of the many medical magazines of the day. Michael invited me to his sophisticated office to ask me to provide the clinical quiz section. I jumped at the chance of joining his team of exceptional journalists, and they became friends as well as colleagues. We had a really happy time until suddenly the whole editorial team was replaced. I don’t yet know the full politics behind the catastrophe, but we regular contributors resigned in sympathy, and the magazine under new management fell apart and disappeared.

Michael was a real star, showing the character integral to the members of the MJA. Other magazines appeared. I was happy to continue my quizzes with Peter Pallot (another of the World Medicine team) in one called Medical Interface, and then in British Medicine, where my quizzes changed into a macabre page called Diagnosis at Post Mortem. Peter was a good friend, and I was thrilled when we heard that the Pallots had a baby son, Richard. Every time I see him reporting on television he reminds me so much of those really happy days.

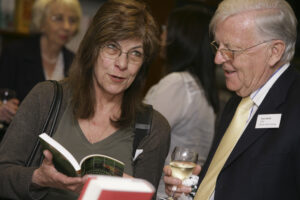

Deanna Wilson and Tom Smith

I branched for a while into the world of district nursing, writing about medical aspects of nursing practice in the Journal of District Nursing, owned by a lovely man called Peter Mell. He sent us two crates of English wine every Christmas, which were much appreciated, but that wasn’t the best part. That was his introduction to me of Deanna Wilson. She subedited my stuff, and in the process made me a much better writer. Deanna has been a close friend ever since, and no one has been more loyal to the MJA than she. When I wrote my humorous (hopefully) books about my life in practice she proofread them, hugely improving them in doing so.

Philippa Pigache, too, joins my list of praise for long time MJA colleagues. Like Deanna she has always been supportive and appreciative, and like Deanna she has made the long journey up to Ayrshire to visit us.

Nothing lasts for ever, and the days of the medical magazines seemed to peter out (sorry for the pun, Peter). In 1977 I moved back to my old practice area in South Ayrshire to be the regular locum for the practices in the southwest of Scotland. The writing continued apace, with regular conference reporting and the writing of books. BBC Scotland picked me up, and they found that I have a good face for radio. Because of the distance, I could only rarely attend MJA meetings in London, and I regret that I’ve been unable to do more. I miss the comradeship and so many old friends, and the always fascinating subjects chosen for the meetings. I hope the current members can forge memories as special as mine. I wish you all well.

What a lovely surprise! A voice from the past recalling the ‘old guard’ of friends and colleagues at the MJA. Tom, we from the south salute you.

Anyone who wants to read something that, in my opinion, out-shines All Creatures Great and Small, should look up Tom’s A Seaside Practice for medical anecdote with jokes.

Thank you Tom for sharing such wonderful stories of the MJA’s early years, and yes, I am sure current members continue to forge strong friendships and fond memories.

One of the very few silver linings of the pandemic has been our move to virtual meetings, which have made it easier for members outside London to take part — and for the first time, the MJA Awards will be livestreamed for those who can’t make it on the evening.

You can find out the winners and help us celebrate excellence in health and medical journalism here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJ03pKQQhok&list=PLfpwqlnyNrvS73FYy_PvyS-eFo0FByjac